Beauregard's Tailor

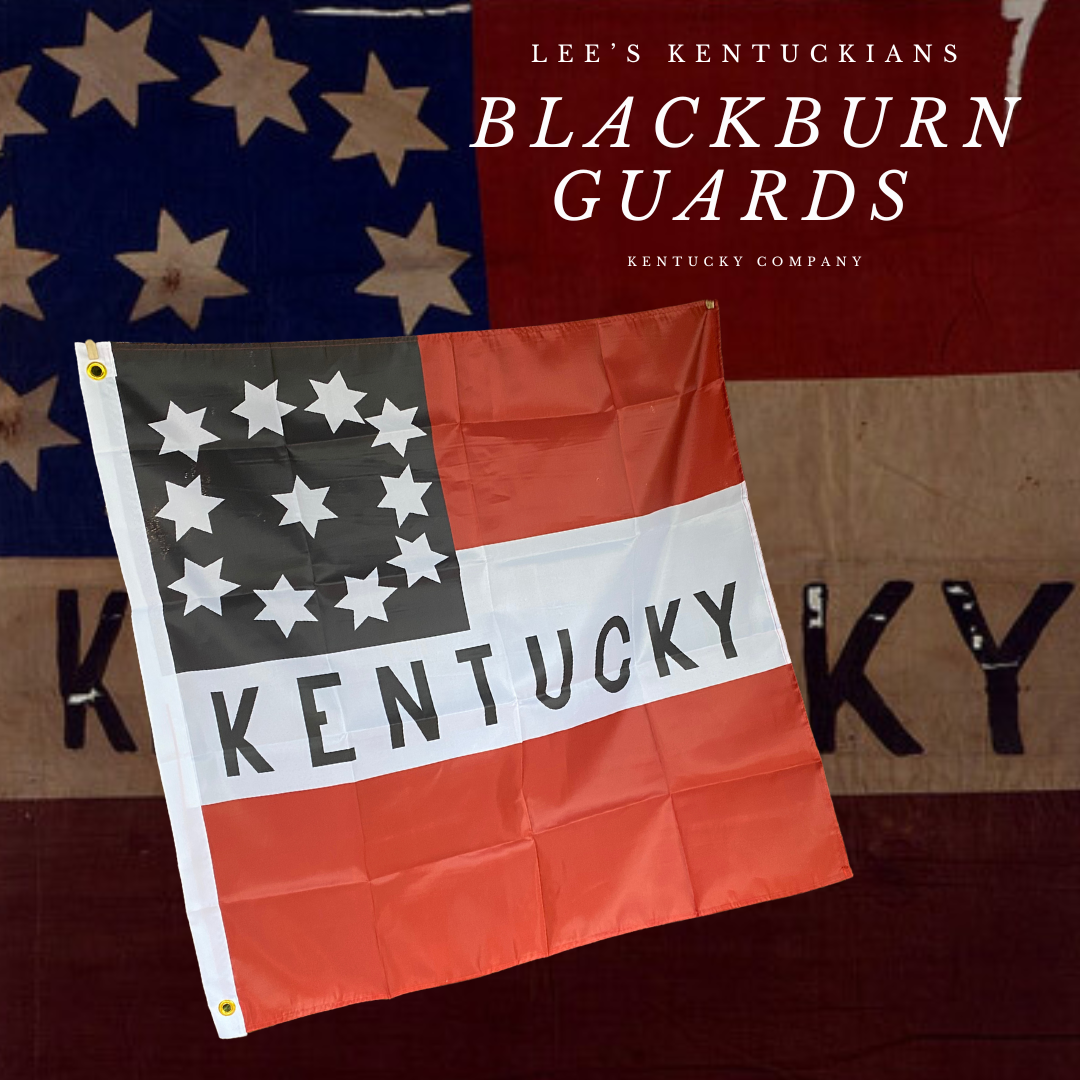

Blackburn Guards - Lee's Kentuckians House Flag

Blackburn Guards - Lee's Kentuckians House Flag

Couldn't load pickup availability

These are modern all-weather nylon flags for your house or garden based on the original flag carried by the Blackburn Guards.

Flag of Company H, 3rd Arkansas Infantry Regiment - the "Blackburn Guards"

Original flag was donated to the former Museum of the Confederacy and is believed to have been the company flag of the Blackburn Guards.

Historical Source:

Most of the Southern states were represented by units in the Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg, but Kentucky is not usually thought of as one of them. However, a Kentucky unit was present at Sharpsburg; the only outfit from that state in Lee's army.

A company of Kentuckians left the Commonwealth early in the summer of 1861 to fight for the Confederacy. Dr. Luke P. Blackburn, later Governor of Kentucky, paid to arm and equip the unit, which called itself the Blackburn Guards. Samuel V. Reid of Covington was the first captain of the company, and led his 29 men off to Virginia1.

The men were accepted into Confederate service at Nashville on June 10, 1861. Companies from Arkansas were passing through Nashville on their way to Virginia, and the Blackburn Guards joined a group of men from Drew County, Arkansas. Reid was probably told that he would have to join with another unit to be accepted into service, since he was far short of the 100 men normally required to make an infantry company.

The company traveled to Virginia, and together with other companies from Arkansas formed the 3rd Arkansas Infantry Regiment at Lynchburg on July 5, 1861. Reid became the captain of Company H, which was made up about equally of Arkansans and the Kentuckians of the Blackburn Guards. The Kentuckians and Arkansans divided the officer and NCO positions equally: fellow Kentuckians became the second lieutenant, first sergeant, and third sergeant of the company. Arkansans filled the other officer and sergeant positions.

The Blackburn Guards thus became the only Kentucky unit to serve in the northern Virginia theater, after the 1st Kentucky Infantry was disbanded in May 1862. The Kentuckians could not have picked a harder-fighting unit to join. The 3rd Arkansas saw action in most of Lee's battles, several times losing over 50 percent casualties. The regiment fought one of its bloodiest battles on September 17, 1862 along the banks of the Antietam Creek at Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle of Antietam was the baptism of fire for most of the Blackburn Guards, though they had been involved in some picket skirmishing in western Virginia in the fall of 1861. They were not engaged in any of the battles of the Peninsula Campaign, and were guarding the defenses of Richmond during Second Manassas. As they set out on September 4 with the rest of Brig. Genl. J. G. Walker's division to join the main army, they were largely untried, and could have no idea of the fierce fighting awaiting them.

The Blackburn Guards crossed the Potomac and advanced to the area of Frederick, Maryland. Walker's Division was then ordered to assist Maj. Genl. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's forces in investing the Union garrison at Harper's Ferry. Upon the surrender of Harper's Ferry on September 15, Walker was again ordered to join the main army, and he reached Sharpsburg on the evening of September 16.

Daylight on September 17 found the 3rd Arkansas over watching a ford on Antietam Creek near the Lower Bridge (soon to become famous as Burnside's Bridge). The Blackburn Guards were observers of an artillery duel between Confederate batteries to their left and Union guns across the stream, but were not engaged during the morning. That would soon change, as they may have judged from the growing roar of battle on the left of the Confederate line.

Around 9:00 A.M. Walker was ordered to take his division to the left and support Jackson's command, which had been under heavy attack in the area of the West Woods, Miller's Cornfield, and the Dunkard Church. As he hastened to Jackson's line, Walker ordered brigade commander Col. Van Manning to leave a force to hold a gap between the West Woods and the left of Maj. Genl. James Longstreet's command, which was defending the Sunken Road area. Manning selected his own regiment, the 3rd Arkansas, and the 27th North Carolina. Col. John R. Cooke of the 27th North Carolina commanded the small semi-brigade; the 3rd Arkansas was commanded by its senior captain, John Reedy2.

Cooke's men halted in a cornfield to the west of the Hagerstown Pike and found themselves immediately under artillery fire. They advanced to a rail fence bordering the cornfield, and opened fire to their left on elements of Greene's Division of the U.S. Twelfth Corps that had forced their way into the West Woods. Cooke had the left companies of the 27th North Carolina fire on infantry and an artillery battery, which withdrew from the West Woods area. He then had his two regiments fall back into the cornfield and lie down3.

When Greene's regiments retreated, Cooke's front was clear, but he could see French's Division of the Union Second Corps advancing on the broken Confederate lines at the Sunken Road to his right front. Undaunted so far by "seeing the elephant" (a Civil War soldiers' term for their first battle), and evidently feeling that his little command was doing well, Cooke decided to advance against French's right, and ordered a charge (or was ordered to advance by Longstreet, as his division commander reported)4. The two small regiments scaled the rail fence, crossed the Hagerstown Pike, and "went at them." They scattered remnants of Greene's troops and took a number of temporary prisoners, whom they directed to stay to the rear as they rushed forward through the fields of farmer Mumma. At one point their advance was so rapid that Cooke ordered his regimental color-bearer to slow down, to which the enthusiastic color-bearer replied, "Colonel, I can't let that Arkansas fellow get ahead of me."5 The Kentuckians, Arkansans and North Carolinians continued to drive toward the right of French's line until they met a stronger force of the enemy posted behind a fence. This was probably the 14th Indiana and 8th Ohio regiments of Kimball's Brigade, French's Division, which had changed front to the right to protect their brigade's flank6. Being almost out of ammunition, isolated, and faced with this larger force, Cooke decided to withdraw. While his division commander thought the withdrawal was done "in the most perfect order,"7 the rearward movement became as impetuous as the advance had been. A North Carolinian reported "we had to pass between two fires" because they were engaged not only by French's regiments, but also by the "perfidy" of the prisoners whom they had taken during the charge, and who now formed and attacked Cooke's men as they withdrew. The 3rd Arkansas and 27th North Carolina soon arrived back at their starting point west of the Hagerstown Pike8. Their attack had probably helped shift the Union focus away from the central part of the battlefield.

The shooting was largely over for the day for the two regiments, mainly due to the fact that they were virtually out of ammunition, but they continued to hold their part of the line. Longstreet reported that "Cooke stood with his empty guns, and waved his colors to show that his troops were in position."9The defiance of Cooke's men, along with other local Confederate counterattacks, shored up the center of the line and helped prevent a possible disaster to the Army of Northern Virginia.

The baptism of fire at Sharpsburg took a terrible toll of the Arkansans and Kentuckians. The 3rd Arkansas did not submit a separate casualty report, but the 27th North Carolina reported 63 percent casualties10, and the losses of the 3rd Arkansas must have been comparable. In the Blackburn Guards, five men were wounded: Joseph M. Applegate, John K. Ball, George B. Dodd, Jesse S. Head (who died in enemy hands on September 26), and George W. Pence. George Pence was captured, and spent months in Federal hospitals until he was paroled11. But they undoubtedly took pride in the part they had played; perhaps some of them may have heard that Genl. Lee himself complimented them, reporting that he saw Cooke's men "standing boldly in line without a cartridge."12

The Kentuckians of the Blackburn Guards soldiered on, but time dwindled their ranks to almost nothing. A number of them were permitted to transfer to other units early in 1863, and others were captured or discharged because of wounds or sickness, and some deserted. When the end came at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, only one of the Kentuckians was still with the 3rd Arkansas: 2nd Lieut. Josephus Miles was adjutant, and surrendered and was paroled with the regiment13.

Researchers today can find few reminders of the Blackburn Guards. The Kentucky Adjutant General's Report mentioned the company, with no explanation of how it came to be part of the 3rd Arkansas. Scattered individual service records remain in the National Archives, and occasional obituaries in Confederate Veteran magazine and local newspapers mention these Kentuckians' service in the Army of Northern Virginia. But the men's war service was a strong influence and evidently fondly remembered: George Pence named two of his sons after Van Manning (colonel of the 3rd Arkansas) and John B. Hood (the Texas Brigade commander); Samuel Matheny's obituary proudly stated that "for four years [he] did noble service for the lost cause."

These flags are made to order and take about 3 weeks to produce and ship.

Shipping Timelines

Shipping Timelines

These flags are made to order and take about 4 weeks to produce and ship.

Share